From birth through maturity to old age, STEPHEN BROOK investigates the life cycle of red Bordeaux and asks how to know when to open that prized bottle.

For many wine lovers, the greatness of a red wine is largely defined by its capacity to age. And not just to age, but to age interestingly. As Hubert de Boüard of Château Angélus puts it: ‘A great wine is a film, not a snapshot.’

Many red wines develop complexity with age – Barolo, Burgundy, Bandol – but Bordeaux pulls off that particular trick more often than most.

Ageability is the stuff of which connoisseurship is made. The old cellar books of former Oxford don Professor Saintsbury and his acolytes were exercises in comparisons of famous vintages; the merits of an 1870 could be played off against the charms of the 1875s. It’s the vinous equivalent of an addiction to Wisden. You would need a chemist to explain precisely why a wine alters as it ages. Probably the most important element is the interaction of oxygen with the wine.

No doubt dry extract, mineral compounds, remaining bacteria in the wine, acidity and alcohol also play their subtle parts. Aromas as well as flavours change with age, and colour may shed its youthful purple robe in favour of a more mellow garnet. One might suppose that a healthy dose of press wine, with its more overt tannins, would also affect ageability, but Anthony Barton of Château Léoville- Barton questions this. ‘When we prepare our blends, we find that the one with a little but not too much press wine is usually the best. But I don’t believe that the proportion of press wine affects longevity one way or the other.’

Bordeaux does not age uniformly. Any time one tastes a wine, it has made a further shift along its line of development. This is frustrating for guidance-hungry consumers when the same wine is rated differently by critics at various stages of its development.

Moreover, subjective factors come into play. It is easy to underestimate – because it’s impossible to quantify – the impact of mood and temperature on tasting. The same row of wines tasted at 15˚C or 18˚C is highly likely to yield different results. Minor impairments such as colds, jet-lag, bad temper and hangovers can alter one’s perception and appreciation.

A claret first becomes available for assessment during the enprimeur tastings (in the year following the vintage), when by definition the wine is only partly formed. Choose an analogy: it’s a sketch, a pre-teen, a child painted in adult clothing by Velázquez. A year or so later the wine is assembled, bottled and released, and ready for a fresh assessment. It’s an adult wine.

After that, endless variables come into play. Some clarets shut down after bottling, sometimes for three years or more. This means their aromas become suppressed, and the fruit quality subdued. One senses the wine rather than enjoys or savours it. But other wines shine out radiantly for a few years after bottling – and then shut down. In a horizontal tasting across a particular vintage, some wines will be less expressive than wines tasted alongside them and, consequently, may be under appreciated. Much depends on the vintage.

‘The bigger the vintage,’ recalls Barton, ‘the longer the shut-down period is likely to be. I remember the 1989 stayed closed for quite a few years. But some other good vintages such as 1985 didn’t shut down that much. And my uncle told me that the great 1929s, which were very long lived, drank well throughout the 1930s.’

Many wines open up at a leisurely pace and then reach a kind of plateau, where they remain frozen in time for around 10 years, sometimes more, before beginning a gentle decline.

That is often the case with the best vintages. Lighter and less structured years, such as 1987, tend to mature more rapidly and then decline more rapidly.

Safe keeping

Once the wine is in bottle, storage becomes important. I recently had the privilege of tasting some very old vintages of Yquem. The bottles came directly from the château, so the wines were at their very best. That is the exception rather than the rule.

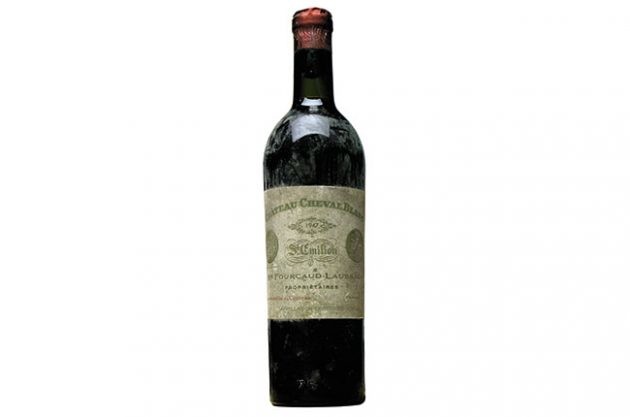

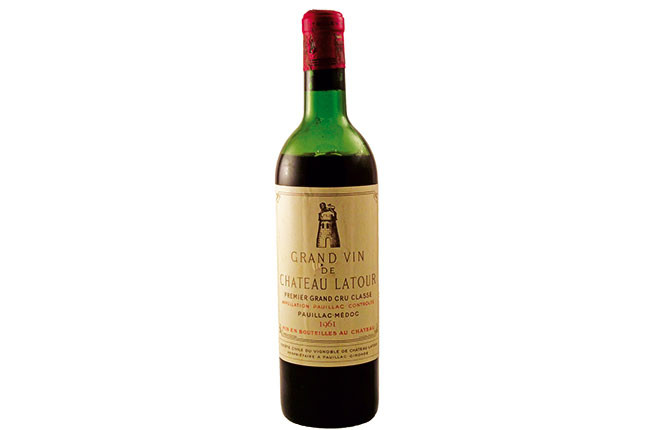

Valued wines, especially first growths, are traded. A mature Lafite bought at auction may have crossed many an ocean from merchant to customer and back again. Most red wines are robust and can take a good deal of punishment, but even a mighty Latour might wilt after an ordeal by heat in a container ship en route for Shanghai.

All this supports the adage that there is no such thing as a great old wine, just a great old bottle. Once a wine has reached maturity, its survival becomes something of a lottery.

Devotees of costly tastings of rare vintages know how frequently a pair of bottles of the same wine can differ enormously, usually as a consequence of storage or cork condition.

As a Bordeaux ages it takes on certain characteristics. Essentially, primary fruit aromas and flavours retreat as more subtle, complex, secondary and tertiary attributes emerge. Aromas of undergrowth or cedar would be typical of a mature or maturing claret; on the palate there may be a growing silkiness and harmony, as elements once separate – oak, acidity, fruit, tannin – start to integrate.

Whether or not you like those secondary and tertiary characteristics will define whether or not you are beguiled by older wines, especially as tones of leather and game become more apparent.

There is no law that states that an old, or mature, wine is ‘better’ than or preferable to a young, fruity wine. Wine lovers who admire the vibrancy and attack of a young claret are entitled to that preference.

Vintage also plays an enormous part in the ageing capacity of Bordeaux. A touch of herbaceousness was often part of the profile of a young claret. Full phenolic ripeness was rare, though global warming and more rigorous viticulture are now making it the rule rather than the exception. But in the past, when harvesting was less selective and the vagaries of an autumnal climate meant that there would usually be some varieties or vineyard blocks that would not ripen fully, a slight greenness was almost inevitable.

If discreet it could, to many palates, be an attractive feature of the wine. But in truly awful years that greenness, rather than adding complexity, suffocated the wine with vegetal aromas. Anyone who has had the misfortune of drinking a 1972 claret will know how unpleasant that can be. In such years, ageing the wine will do nothing to repair it. To age successfully, a Bordeaux must be from a good vintage and must be reasonably well balancedat the outset.

It is worth bearing in mind the saying of John Williams of Frog’s Leap estate in Napa: ‘Ugly young, ugly old.’ There’s a lot of truth in that.

Some wines that are very oaky or very tannic in their youth may blossom, after a decade or two, into complex rather than merely oaky wines, nobly structured rather than merely tannic.

It is, however, exceedingly difficult to predict whether a youthful imbalance will remedy itself with time, or become permanent disfigurement. The 1975 vintage was a case in point. The young wines were ferociously tannic. The trade mostly had confidence in them, acclaiming the vintage as a great one but saying that it simply required time for the tannins to soften.

In a few cases, they did; La Mission Haut-Brion and Pétrus, for instance, are excellent 1975s. But most wines from that vintage remained tough as nails and never became enjoyable.

The right moment

Every winemaker, and many a wine writer, is often asked when is the ‘right’ moment to drink a particular bottle. The answer is that there is no such thing. If you have three bottles of a fine Bordeaux from the same year, chances are you will drink the first too young, the second at a moment when it gives great pleasure, and the third when it is in decline. But those moments can only be defined by personal taste. My moment of perfection may not be the same as yours, and vice versa.

It is entirely legitimate to enjoy a great wine in its virile, imposing youth. It is equally legitimate to enjoy it during its mellow middle age – at, say, 20 years. After 30 years, the risk factor increases significantly. The chances of a wine, however great the property or vintage, being faulty are far greater at, say, 40 or 50 years.

Oxidation, cork taint, poor storage, different bottlings (château bottling was the exception rather than the rule until the 1960s or beyond) can all gang up to mug a wine’s evolution. Opening a venerable bottle, especially one acquired at great expense, is an act of faith not always rewarded. I recall watching a duff bottle of 1953 Château Margaux being tipped down the sink.

Some wine merchants and specialists organise vertical tastings that often include wines from the 19th century or 1920s. These events don’t come cheap but they offer an opportunity to taste legendary vintages for less than the price of a single bottle.

For wines from good, if not stellar, vintages such as 1978, 1985, 1988 and 1995, there are rich pickings at auction houses, with prices often lower than the grossly inflated prices of some modern vintages.

Translated by Sylvia Wu / 吴嘉溦

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit